The story of Jesus in the New Testament does oddly capture attention—a man of compassion, who heals, teaches, dies, and rises again, bringing a message of hope and renewal. Yet older writings from over a century ago reveal something intriguing: many elements in this account seem to mirror ideas and images from Egyptian mythology, as if the Gospel writers drew from a much older stream of human imagination about its divine figure and salvation.

Gerald Massey, in The Historical Jesus and the Mythical-Christ, carefully laid out his case. He separated a possible real person—Jehoshua Ben-Pandira, a teacher mentioned in the Talmud, executed as a sorcerer around 70 BCE or earlier—from the "mythical Christ" described in the Gospels. Massey focused on the virgin birth as one clear link. In Egyptian tradition, this idea appears in temple art long before Christianity. At the Temple of Luxor, built under Pharaoh Amenhotep III in the 18th Dynasty (around 1400 BCE), wall reliefs show a divine conception and birth (something I have already blogged about). The maiden queen Mut-em-ua receives an announcement from the god Thoth (the ibis-headed scribe and herald), then conceives a child who becomes the divine king. These scenes include an annunciation, a miraculous union involving the god Amun, the shaping of the child on a potter's wheel by Khnum, and the birth itself, attended by protective deities.

Massey saw this sequence—annunciation, divine impregnation without ordinary means, shaping of the child, and sacred birth—as a longstanding pattern and blueprint for how the eternal child enters the world through a virgin-like mother (a pattern that cannot arise from ordinary human events but lives in myth and symbol). He argued that the Gospel virgin birth echoes this ancient motif, where the divine enters the world through a pure vessel, untouched by ordinary generation.

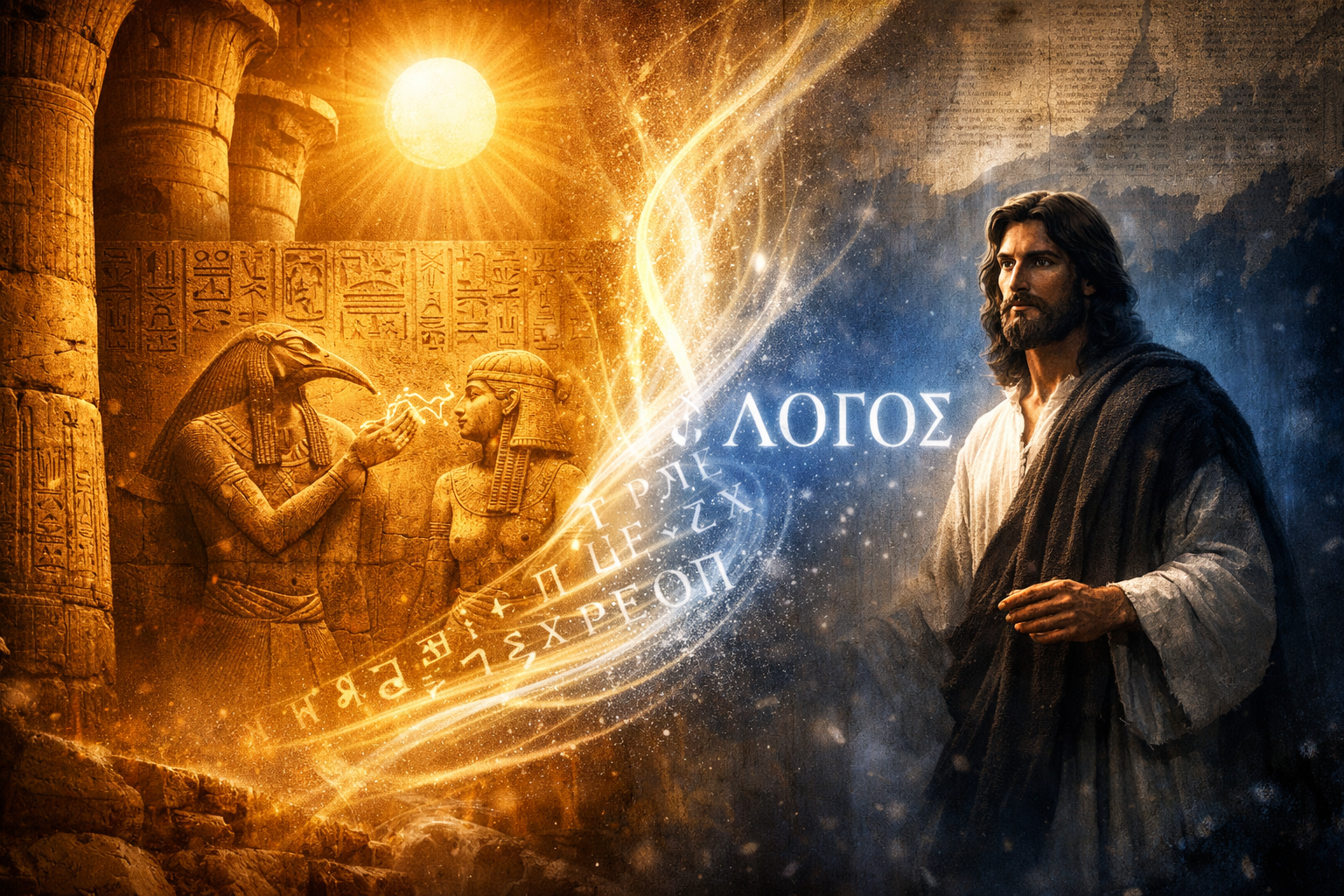

Alice Grenfell, in her article "Egyptian Mythology and the Bible" in The Monist, explored other connections, especially around creation and the power of speech. In Genesis, God creates by speaking: "Let there be light," and it happens. Grenfell connected this to the Egyptian idea of maat kheru (or maa kheru), the "true voice" or creative utterance. Gods and the blessed dead wield this power to bring things into existence—light from their eyes, reality from their words. She noted how the goddess Maat, linked to light and truth, represents this creative force. The offering of Maat to a god becomes a ritual of returning reality to its source.

This idea surfaces again in the Gospel of John: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God... All things were made by him." The Logos as creator through speech feels oddly close to the Egyptian view that naming and speaking aloud turns potential into being. Grenfell even pointed to Joseph's Egyptian name, Zaphnath-paaneah ("The god spoke, and he lives"), as carrying the same tradition of divine voice granting life.

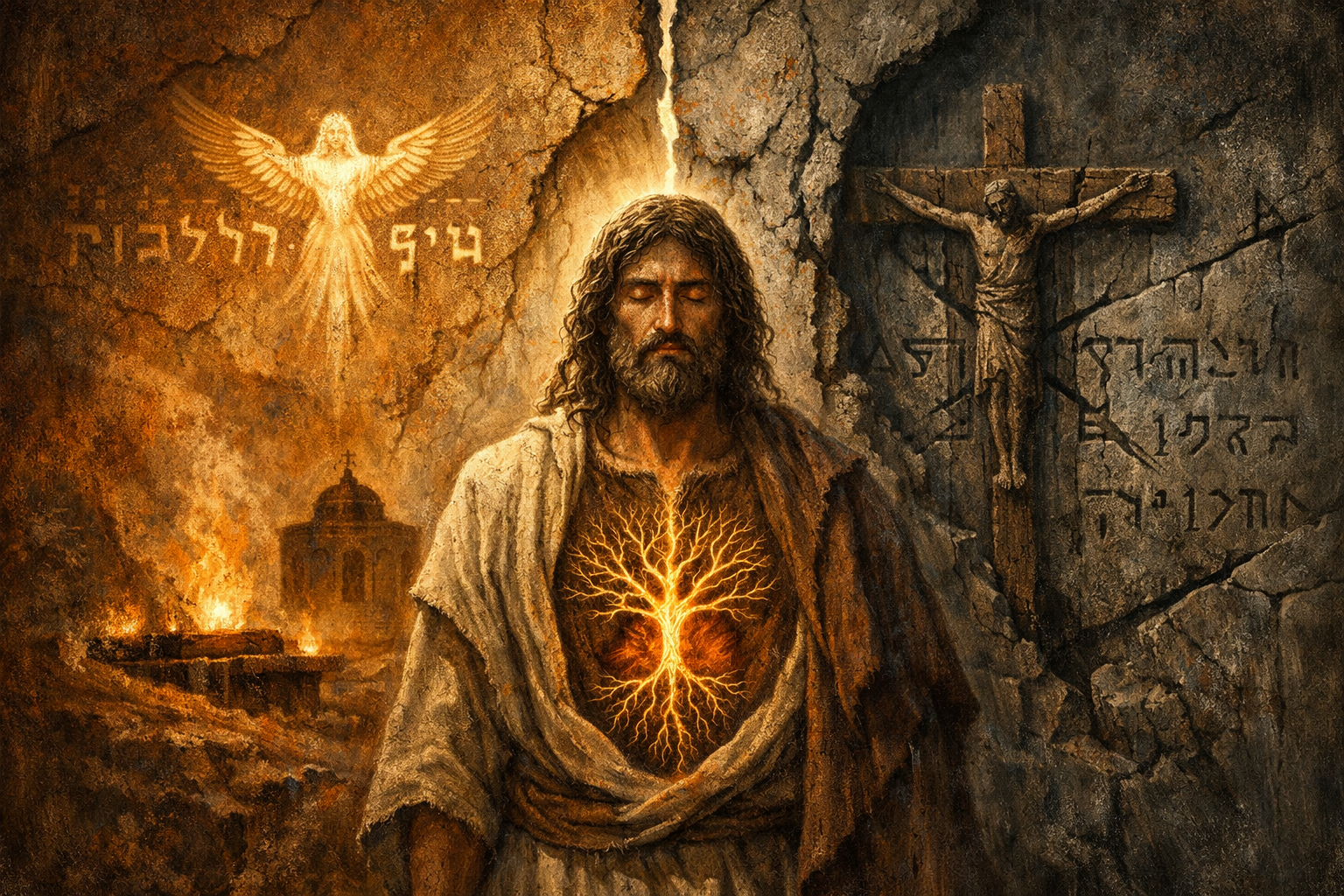

These parallels do not erase the uniqueness of the New Testament account; all of these myths and their sayings carry their own unique essence. Instead, they suggest that when early Christians shaped their story of the Jesus character, they reached for symbols that already carried deep meaning for people familiar with older traditions. The virgin birth, the divine word bringing life, the savior who overcomes death—these motifs had circulated for centuries along the Nile, expressing humanity's hope for something greater than ordinary existence. To re-hash the same mythology in a new way doesn’t make it any more valid or historical, but serves to open our mind to the allegory that has been passed down.

What emerges is a sense of continuity: ancient Egyptians carved their longing for “divine intervention” into stone, and later writers found ways to express a similar longing through the character of Jesus. The story feels both ancient and fresh, rooted in shared human questions about birth, light, and renewal.

Yet these parallels refuse to sit quietly. To what extent did earlier myths shape the telling of the Jesus narrative? If the story emerged from a distinctly Hebrew or Hellenistic Jewish setting, why does it resonate so strongly with motifs far older and geographically distant? What additional strands from Egypt—or other ancient cultures—remain tied to the New Testament? Looking into these questions invites us to see the Gospels not as literal historical reports, but as participants in a much older allegorical dialogue stretching across civilizations. In that light, the Jesus character may function less as a purely biographical construction and more as a literary embodiment of symbolic truths, crafted to convey meaning through the language of myth, theology, and cultural memory.

CLICK: The Myth of the Virgin Birth and Its Allegory Explained

References

Grenfell, A. (1906). EGYPTIAN MYTHOLOGY AND THE BIBLE. The Monist, 16(2), 169–200.

Massey, G. (1900). The Historical Jesus and Mythical-Christ.

Sharpe, S. (1863). EGYPTIAN MYTHOLOGY AND EGYPTIAN CHRISTIANITY. In JOHN RUSSELL SMITH. JOHN RUSSELL SMITH.